The Rat Race We Actually Won - Building Smart Cage

The Problem: Why Smart Pest Management?

It started, as many good engineering stories do, with a phone call from someone frustrated.

“We have 200 rat traps spread across a warehouse the size of four football fields,” the operations manager told us. “Every morning, my team spends three hours walking the floor, checking each one. Half the time, they’re empty. Sometimes a trap sits triggered for days before anyone notices. And don’t even get me started on the bait situation.”

He paused, then delivered the line that would consume our next six months: “There has to be a better way.”

There was. We just had to build it.

Large-scale warehouses and godowns face a persistent challenge: pest control. Traditional rat traps, while effective, come with significant operational overhead. Facility managers typically deploy dozens—sometimes hundreds—of traps across vast spaces, creating a maintenance nightmare.

The Traditional Approach Has Critical Flaws:

Picture this: a 400,000 square foot godown in the industrial outskirts, filled floor-to-ceiling with goods that rats find absolutely delightful. Grain shipments. Textile bales. Cardboard. For the local rodent population, it’s basically a five-star resort.

The traditional approach to pest control here was brute force. Scatter traps everywhere. Send humans to check them. Repeat forever. It worked, sort of, in the same way that checking every mailbox in a city works if you’re trying to find one specific letter.

Manual inspection rounds are time-consuming and inefficient. A single warehouse might require hours of daily inspection time just to check trap status. Traps with captured rodents left unattended create hygiene issues and reduce trap effectiveness. Bait freshness is difficult to track, leading to either wasteful over-replacement or ineffective stale bait. There’s no data-driven insight into pest activity patterns, hotspots, or seasonal trends.

The problems were obvious once you started counting:

Time: Three hours of inspection daily meant 15 hours per week, 780 hours per year—nearly a fifth of a full-time employee’s annual hours, spent walking and looking at empty cages.

Response lag: A triggered trap might sit for 48 hours before discovery. In that time, other rats learn to avoid the area, and the captured rodent becomes a hygiene issue rather than a pest control victory.

Bait blindness: Nobody was tracking when bait was placed. Some traps had fresh bait weekly; others had the same dried-out chunk of whatever for months. Stale bait catches nothing except dust.

Zero intelligence: After years of operation, the facility knew nothing about pest patterns. Which areas had more activity? What times? What seasons? The data existed—in the form of individual trap checks—but it was never captured, never analyzed, never used.

We weren’t just building a notification system. We were building the nervous system for a warehouse that had been operating blind.

The Business Impact:

Each hour spent on manual inspection is an hour not spent on core operations. Undetected pest activity can lead to inventory damage, compliance violations, and reputation risk. Without analytics, preventive measures remain guesswork rather than strategy.

Enter Smart Cage

Our solution transforms passive rat traps into intelligent, connected devices that report their status in real-time. Facility managers gain instant visibility into trap status, bait freshness, and movement patterns—all from a centralized dashboard. The result is faster response times, optimized bait management, and actionable insights into pest behavior patterns.

Solution Overview

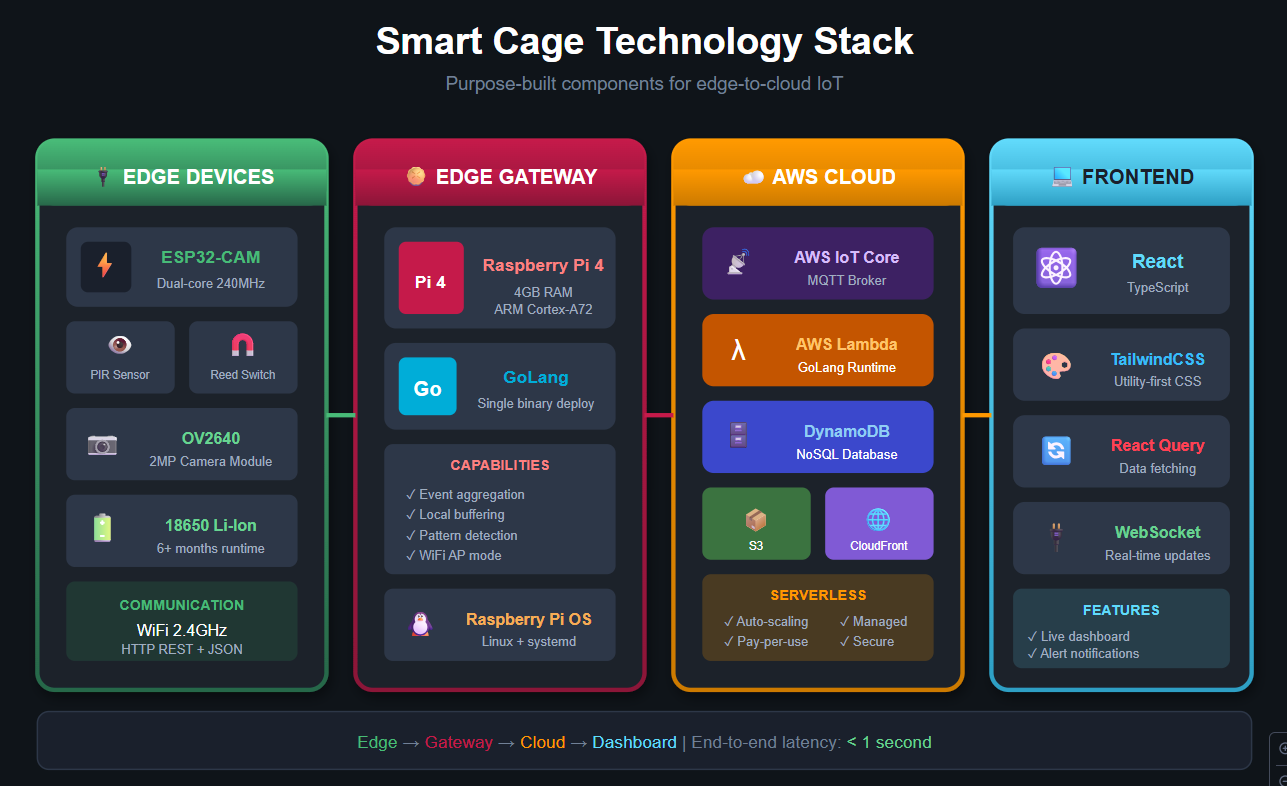

Smart Cage is a comprehensive IoT ecosystem consisting of three primary layers: the edge devices (smart traps), the edge gateway (Raspberry Pi), and the cloud backend (AWS serverless infrastructure).

Every IoT project is really three projects duct-taped together: the devices that sense things, the system that thinks about what they sensed, and the interface that lets humans understand what’s happening. Get any one of these wrong, and the whole thing collapses.

We started with first principles. What did we actually need to know about each trap?

Is something caught? The existential question. Binary, urgent, time-sensitive.

Is anything moving nearby? Leading indicator. A trap with lots of movement but no catches might be poorly positioned—or might be about to get very busy.

Is the bait still good? Operational hygiene. Traps need feeding too.

Is the device still alive? Meta-question. A silent trap might mean no rats, or it might mean a dead battery. These are very different situations.

From these questions, our architecture emerged organically. Each trap would become a “Smart Cage”—a self-contained sensor package that could answer all four questions. These would talk to local hubs (Raspberry Pis, one per zone) that would aggregate, process, and relay information to the cloud. And in the cloud, a serverless backend would store, analyze, and present everything through a dashboard that could be accessed from anywhere.

Simple in concept. The devil, as always, was in the implementation.

Core Capabilities:

The system provides real-time trap status monitoring, detecting capture events within seconds and alerting maintenance staff immediately. Motion detection and logging through integrated cameras tracks rodent activity patterns even when traps aren’t triggered. Bait freshness tracking automatically monitors when bait was last placed and alerts when replacement is needed. The centralized dashboard visualization displays all cage statuses, alerts, and analytics in a unified ReactJS interface. Historical analytics enable trend analysis to identify hotspots, peak activity times, and optimize trap placement.

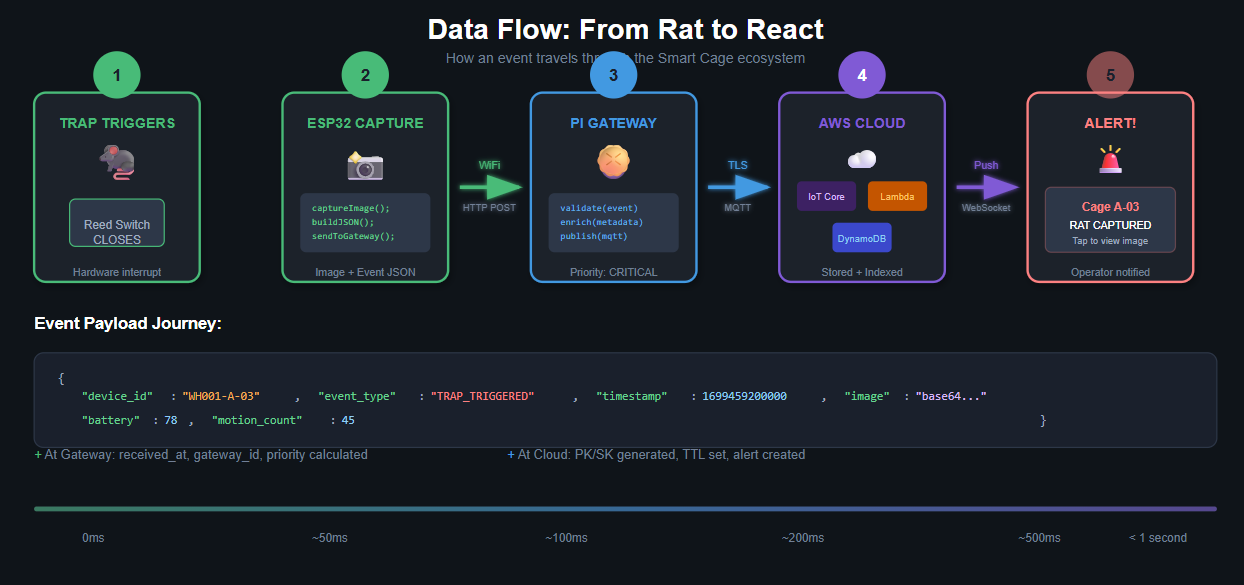

The Data Flow:

Each smart cage contains sensors and a camera module that communicate with a local Raspberry Pi over WiFi. The Pi aggregates data from all connected cages, processes events locally, and publishes relevant data to AWS IoT Core. Lambda functions process incoming data and persist it to DynamoDB. The ReactJS dashboard, served via CloudFront and S3, provides real-time visibility to operators.

Technology Stack & Justification

Edge Devices

ESP32 Microcontrollers serve as the brain of each smart cage. The ESP32 was chosen for its built-in WiFi and Bluetooth capabilities eliminating the need for separate communication modules, its ultra-low power consumption critical for battery-powered deployments, its sufficient processing power for local sensor management and image capture, and its cost-effectiveness at scale when deploying hundreds of cages.

PIR Motion Sensors (HC-SR501) detect movement around and within the cage. These sensors offer excellent sensitivity with adjustable range, very low power consumption in standby mode, and a simple digital output interface with the ESP32.

Mechanical Trap Sensors (Reed Switch + Magnet) provide binary trap status—open or triggered. The reed switch solution is extremely reliable with no moving electronic parts, instant response time, and near-zero power consumption.

ESP32-CAM Module captures images when motion is detected. This choice provides sufficient resolution for activity verification, built-in microSD support for local buffering, and direct WiFi capability for image transmission.

Edge Gateway

Raspberry Pi 4 (4GB) serves as the local aggregation and processing hub. The Raspberry Pi provides sufficient compute power for real-time data processing from 50+ cages, built-in WiFi for network management, GPIO pins for direct sensor integration if needed, a mature Linux ecosystem for reliable 24⁄7 operation, and a low cost relative to industrial gateways.

GoLang was selected for the edge software for several compelling reasons. GoLang compiles to a single binary with no runtime dependencies, simplifying deployment. It offers excellent performance for concurrent operations essential when managing multiple device connections. The low memory footprint is important for resource-constrained edge devices. GoLang provides strong standard library support for networking and JSON processing, and cross-compilation makes it easy to build for ARM architecture.

Cloud Infrastructure

AWS IoT Core provides the MQTT broker and device management layer. It offers managed MQTT with automatic scaling, built-in device authentication and authorization, seamless integration with other AWS services, and a rules engine for real-time data routing.

AWS Lambda (GoLang) handles serverless compute. Using GoLang for Lambda maintains language consistency with edge code, delivers the fastest cold-start times among Lambda runtimes, and provides cost efficiency with pay-per-invocation pricing.

Amazon DynamoDB serves as the NoSQL database for device data. DynamoDB provides single-digit millisecond latency at any scale, a flexible schema accommodating varied sensor data, built-in TTL for automatic data expiration, and seamless integration with Lambda.

Amazon S3 + CloudFront hosts and delivers the ReactJS dashboard with global edge distribution for low latency, built-in HTTPS and caching, and cost-effective static hosting.

ReactJS powers the dashboard frontend. React enables component-based architecture perfect for modular dashboard widgets, a rich ecosystem of charting and visualization libraries, real-time updates via WebSocket integration, and strong TypeScript support for maintainable code.

High-Level Architecture

Architecture Principles:

The design follows an edge-first processing philosophy where data is processed at the edge to minimize bandwidth and latency, with only meaningful events transmitted to the cloud. The event-driven architecture means each component reacts to events rather than polling, reducing resource consumption. The serverless backend eliminates infrastructure management with automatic scaling based on demand. Loose coupling ensures each component can be updated or replaced independently.

Edge Devices: Smart Cage Sensors

Hardware Configuration

Each smart cage contains an integrated sensor module with the following components:

The heart of each Smart Cage is an ESP32 microcontroller—a tiny, wifi-enabled computer that costs about as much as a fancy coffee. We chose it over alternatives like Arduino (no built-in wifi) or Raspberry Pi Zero (overkill and power-hungry) because it hit the sweet spot: enough capability to run our sensing logic, built-in connectivity, and miserly power consumption that lets it run for months on batteries.

Mounted on each ESP32, we attached three sensing systems:

The Reed Switch: This is the trap trigger detector—beautifully simple, almost stupidly reliable. A reed switch is just two metal contacts sealed in a glass tube that close when a magnet is nearby. We mount the magnet on the trap’s door and the switch on the frame. Door closes? Circuit completes. Rat caught. No software involved, no false positives from temperature changes or vibration. Physics doing the work.

The PIR Sensor: A passive infrared motion detector, the same technology that turns on your porch light when you walk by. It detects the heat signature of warm-blooded creatures moving through its field of view. We use it to track activity around each trap—not because we need to know every time a rat walks by, but because the pattern of movement tells a story. Heavy traffic with no catches? Wrong bait, wrong placement, or clever rats. Sudden spike in activity after months of quiet? New infestation vector identified.

The Camera: An ESP32-CAM module—essentially the same ESP32 chip with a small camera attached. This was controversial during design. It adds cost, complexity, and power draw. But it’s also our verification layer. When a trap triggers, we grab a photo. This lets operators confirm catches remotely and, more importantly, builds a visual dataset for future machine learning work. (Yes, we’re training a model to identify rat species. No, we’re not proud of how many rat photos we’ve now looked at.)

Each Smart Cage also has its own identity—a unique ID burned into permanent

memory during provisioning. The naming scheme we landed on is hierarchical:

WH001-A-042 tells you the warehouse (WH001), the zone (A), and the cage number

(042). This matters more than you’d think. When you have 200 devices screaming

for attention, knowing exactly which physical trap needs service is the

difference between a five-minute fix and a twenty-minute scavenger hunt.

Device Identification

Each cage is uniquely identified using a hierarchical naming scheme:

Format: {facility_id}-{zone}-{cage_number}

Example: WH001-A-042

Where:

- facility_id: Unique warehouse identifier (WH001, WH002, etc.)

- zone: Physical zone within the warehouse (A, B, C, etc.)

- cage_number: Sequential cage number within the zone (001-999)

This identifier is burned into the ESP32’s NVS (Non-Volatile Storage) during provisioning.

ESP32 Firmware

The firmware that runs on each cage is where hardware meets software. It’s a few thousand lines of C++ that turn raw sensor signals into meaningful events. Let’s walk through how it works.

Setting Up the Essentials

First, we import the libraries we need. Think of these as the toolbox—each one gives us a specific capability:

// smart_cage_firmware.ino

#include <WiFi.h>

#include <HTTPClient.h>

#include <ArduinoJson.h>

#include <esp_camera.h>

#include <Preferences.h>

WiFi for connectivity, HTTPClient for talking to the gateway, ArduinoJson for packaging our data, esp_camera for image capture, and Preferences for storing configuration that survives power cycles.

Defining Our World

Next, we map out the physical connections and set some ground rules:

// Pin Definitions

#define PIR_PIN 13

#define REED_SWITCH_PIN 12

#define LED_STATUS 4

// Configuration

#define GATEWAY_HOST "192.168.4.1"

#define GATEWAY_PORT 8080

#define MOTION_COOLDOWN 5000 // 5 seconds between motion events

These pin numbers tell the ESP32 which physical connections correspond to which sensors. The motion cooldown is important—without it, a single rat walking by would trigger dozens of events as it moved through the sensor’s field of view. We’re interested in that a rat was there, not in tracking its every wiggle.

State Variables: Memory That Matters

The firmware needs to remember a few things between loop iterations. Some of

these variables are marked volatile because they’re modified by interrupt

handlers—hardware events that can fire at any moment:

// Device Identity

Preferences preferences;

String deviceId;

String facilityId;

String zone;

// State tracking

volatile bool trapTriggered = false;

volatile bool motionDetected = false;

unsigned long lastMotionTime = 0;

unsigned long lastBaitRefresh = 0;

int motionCount = 0;

The volatile keyword tells the compiler “this value might change behind your

back”—critical when dealing with hardware interrupts. The rest track operational

state: when did we last see motion? How many events since the last reset? When

was the bait refreshed?

Interrupt Handlers: Responding to the Real World

Hardware interrupts are how we react instantly to events. When the trap door closes or motion is detected, these functions fire immediately—no waiting for the main loop:

// Interrupt handlers

void IRAM_ATTR onTrapTrigger() {

trapTriggered = true;

}

void IRAM_ATTR onMotionDetect() {

if (millis() - lastMotionTime > MOTION_COOLDOWN) {

motionDetected = true;

lastMotionTime = millis();

}

}

Notice how minimal these are. Interrupt handlers should be fast—set a flag and

get out. The actual work happens in the main loop. The IRAM_ATTR annotation

tells the compiler to put these functions in fast RAM for instant execution.

Initialization: Waking Up and Getting Oriented

When the ESP32 powers on, setup() runs once. This is where we configure

everything and establish our identity:

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200);

// Load device identity from NVS

preferences.begin("smartcage", true);

deviceId = preferences.getString("device_id", "UNKNOWN");

facilityId = preferences.getString("facility_id", "WH001");

zone = preferences.getString("zone", "A");

preferences.end();

// Initialize pins

pinMode(PIR_PIN, INPUT);

pinMode(REED_SWITCH_PIN, INPUT_PULLUP);

pinMode(LED_STATUS, OUTPUT);

// Attach interrupts

attachInterrupt(digitalPinToInterrupt(REED_SWITCH_PIN), onTrapTrigger, FALLING);

attachInterrupt(digitalPinToInterrupt(PIR_PIN), onMotionDetect, RISING);

// Initialize camera

initCamera();

// Connect to gateway WiFi

connectToGateway();

Serial.printf("Smart Cage %s initialized\n", deviceId.c_str());

}

The device identity comes from non-volatile storage—configuration that was

burned in during provisioning and survives power loss. The INPUT_PULLUP on the

reed switch means “normally high, goes low when triggered”—a common pattern for

simple switches.

Camera Initialization: Getting Eyes

The ESP32-CAM has a surprising number of configuration options. Here’s how we set it up for our use case:

void initCamera() {

camera_config_t config;

config.ledc_channel = LEDC_CHANNEL_0;

config.ledc_timer = LEDC_TIMER_0;

config.pin_d0 = 5;

config.pin_d1 = 18;

config.pin_d2 = 19;

config.pin_d3 = 21;

config.pin_d4 = 36;

config.pin_d5 = 39;

config.pin_d6 = 34;

config.pin_d7 = 35;

config.pin_xclk = 0;

config.pin_pclk = 22;

config.pin_vsync = 25;

config.pin_href = 23;

config.pin_sscb_sda = 26;

config.pin_sscb_scl = 27;

config.pin_pwdn = 32;

config.pin_reset = -1;

config.xclk_freq_hz = 20000000;

config.pixel_format = PIXFORMAT_JPEG;

config.frame_size = FRAMESIZE_VGA;

config.jpeg_quality = 12;

config.fb_count = 1;

esp_err_t err = esp_camera_init(&config);

if (err != ESP_OK) {

Serial.printf("Camera init failed: 0x%x\n", err);

}

}

Most of this is pin mapping—telling the ESP32 which GPIO pins connect to which camera signals. The important settings are at the bottom: VGA resolution (good enough for verification, not so large it kills our bandwidth), JPEG compression at quality 12 (balancing file size with image clarity), and a single frame buffer (keeps memory usage low).

Handling a Trap Trigger: The Critical Path

When a trap catches something, this is what happens. Speed matters here—we want to capture the event while it’s still relevant:

void handleTrapEvent() {

digitalWrite(LED_STATUS, HIGH);

// Capture image

camera_fb_t* fb = esp_camera_fb_get();

// Build event payload

StaticJsonDocument<1024> doc;

doc["device_id"] = deviceId;

doc["facility_id"] = facilityId;

doc["zone"] = zone;

doc["event_type"] = "TRAP_TRIGGERED";

doc["timestamp"] = millis();

doc["battery_level"] = getBatteryLevel();

// Send to gateway

sendEvent(doc, fb);

if (fb) esp_camera_fb_return(fb);

digitalWrite(LED_STATUS, LOW);

}

We light up the status LED (useful for debugging during deployment), grab a photo, package everything into a JSON document, and ship it to the gateway. The frame buffer gets returned to free memory—camera images are big, and we don’t want to leak memory on a device with only 520KB of RAM.

Motion Detection: The Quieter Event

Motion events are more frequent and less urgent. We handle them more conservatively:

void handleMotionEvent() {

motionCount++;

// Only capture image every 10th motion event to save power

camera_fb_t* fb = nullptr;

if (motionCount % 10 == 0) {

fb = esp_camera_fb_get();

}

StaticJsonDocument<512> doc;

doc["device_id"] = deviceId;

doc["facility_id"] = facilityId;

doc["zone"] = zone;

doc["event_type"] = "MOTION_DETECTED";

doc["timestamp"] = millis();

doc["motion_count"] = motionCount;

sendEvent(doc, fb);

if (fb) esp_camera_fb_return(fb);

}

We increment a counter but only capture an image every tenth event. This is a power optimization—the camera draws significant current, and we don’t need photographic evidence of every rat that walks by. The motion count itself tells us what we need to know about activity levels.

WiFi Connection: Getting Online

Connecting to the gateway’s WiFi network is straightforward, but we add retry logic because industrial environments are electrically noisy:

void connectToGateway() {

WiFi.begin("SmartCage-Gateway", "SecureP@ss2024!");

int attempts = 0;

while (WiFi.status() != WL_CONNECTED && attempts < 30) {

delay(500);

Serial.print(".");

attempts++;

}

if (WiFi.status() == WL_CONNECTED) {

Serial.printf("\nConnected to gateway. IP: %s\n",

WiFi.localIP().toString().c_str());

}

}

Thirty attempts with half-second delays gives us 15 seconds to connect. If we can’t connect after that, something’s genuinely wrong—the gateway might be down, or this device might be too far away. The main loop will keep trying periodically.

The Heartbeat: Staying Alive

Every five minutes, each cage sends a heartbeat—a status update proving it’s still operational:

void sendHeartbeat() {

StaticJsonDocument<512> doc;

doc["device_id"] = deviceId;

doc["facility_id"] = facilityId;

doc["zone"] = zone;

doc["event_type"] = "HEARTBEAT";

doc["timestamp"] = millis();

doc["battery_level"] = getBatteryLevel();

doc["trap_status"] = digitalRead(REED_SWITCH_PIN) == LOW ? "TRIGGERED" : "ARMED";

doc["motion_count_since_reset"] = motionCount;

doc["last_bait_refresh"] = lastBaitRefresh;

doc["wifi_rssi"] = WiFi.RSSI();

sendEvent(doc, nullptr);

}

This comprehensive status update includes everything: battery level (are we dying?), trap status (did we catch something and nobody noticed?), accumulated motion count (how busy has this location been?), bait age (does this need refreshing?), and WiFi signal strength (is connectivity degrading?). It’s our “all systems nominal” check-in.

Sending Events: The Transmission Layer

This function does the actual work of transmitting data to the gateway:

void sendEvent(JsonDocument& doc, camera_fb_t* image) {

if (WiFi.status() != WL_CONNECTED) return;

HTTPClient http;

http.begin(String("http://") + GATEWAY_HOST + ":" + GATEWAY_PORT + "/api/events");

http.addHeader("Content-Type", "application/json");

String jsonPayload;

serializeJson(doc, jsonPayload);

// If image exists, encode as base64 and add to payload

if (image != nullptr) {

// Image handling - base64 encode and append

// (simplified for brevity)

}

int httpCode = http.POST(jsonPayload);

if (httpCode != 200) {

Serial.printf("Event send failed: %d\n", httpCode);

}

http.end();

}

We use HTTP POST because it’s simple and debuggable. In production, MQTT would be more efficient, but HTTP means we can test endpoints with curl and see exactly what’s being sent. The base64 image encoding is omitted here for clarity—it’s just the standard approach of converting binary data to text for JSON transmission.

Battery Monitoring: Staying Powered

Knowing when batteries are dying is critical in remote deployments:

float getBatteryLevel() {

// Read ADC for battery voltage

int raw = analogRead(34);

float voltage = (raw / 4095.0) * 3.3 * 2; // Voltage divider factor

float percentage = ((voltage - 3.0) / (4.2 - 3.0)) * 100;

return constrain(percentage, 0, 100);

}

We read the analog voltage through a voltage divider (can’t directly read

battery voltage—it might exceed the ESP32’s 3.3V maximum input), convert to

actual voltage, then map the typical LiPo battery range (3.0V empty, 4.2V full)

to a percentage. The constrain function prevents weird values if our math goes

outside reasonable bounds.

Bait Refresh Acknowledgment

When maintenance staff refresh the bait, they can log it through the dashboard. That triggers this callback on the device:

// Bait refresh acknowledgment (called via HTTP endpoint)

void acknowledgeBaitRefresh() {

lastBaitRefresh = millis();

motionCount = 0; // Reset motion counter

// Store in NVS for persistence

preferences.begin("smartcage", false);

preferences.putULong("last_bait", lastBaitRefresh);

preferences.end();

}

We timestamp the refresh and reset the motion counter (fresh bait should attract more activity—we want to measure that from zero). Storing it in non-volatile storage means even if the device reboots, we remember when the bait was last changed.

The Main Loop: Orchestrating Everything

Finally, the main loop ties it all together. This runs continuously, checking for events and managing periodic tasks:

void loop() {

// Handle trap trigger event (highest priority)

if (trapTriggered) {

handleTrapEvent();

trapTriggered = false;

}

// Handle motion detection

if (motionDetected) {

handleMotionEvent();

motionDetected = false;

}

// Periodic heartbeat (every 5 minutes)

static unsigned long lastHeartbeat = 0;

if (millis() - lastHeartbeat > 300000) {

sendHeartbeat();

lastHeartbeat = millis();

}

// Check WiFi connection

if (WiFi.status() != WL_CONNECTED) {

connectToGateway();

}

delay(100);

}

The priority order matters: trap triggers are handled first (most urgent), then motion, then housekeeping tasks like heartbeats and connectivity checks. The 100ms delay at the end prevents the loop from spinning too fast and wasting power. Most of the time, this loop just checks a few boolean flags and goes back to sleep.

Communication Protocol

Devices communicate with the Raspberry Pi using a simple REST API over HTTP. While MQTT would be more efficient for production, HTTP simplifies debugging and works well for the expected message frequency.

Event Payload Schema:

{

"device_id": "WH001-A-042",

"facility_id": "WH001",

"zone": "A",

"event_type": "TRAP_TRIGGERED | MOTION_DETECTED | HEARTBEAT | BAIT_REFRESHED",

"timestamp": 1699459200000,

"battery_level": 87.5,

"trap_status": "ARMED | TRIGGERED",

"motion_count": 156,

"wifi_rssi": -67,

"image_data": "base64_encoded_jpeg..."

}

Edge Gateway: The Raspberry Pi Hub

Typically the godowns are miles away from the back office. And the big boss sitting there wants to know what the idiots are doing on the floor. (Both genuinely feel so about each other.)

The Local Brain: Why a Raspberry Pi in the Middle

Here’s a question that seems obvious until you think about it: why not just have each cage talk directly to the cloud?

The answer is resilience, bandwidth, and intelligence.

Resilience: Warehouse wifi is terrible. Metal shelving creates dead zones. Forklifts cause interference. If each cage needs a direct internet connection to function, any network hiccup means lost data—or worse, a triggered trap that never reports in. By routing through a local Raspberry Pi, we create a buffer. The cages only need to reach the Pi (which we control), and the Pi handles the unreliable journey to the internet.

Bandwidth: 200 cages sending heartbeats every five minutes is 40 messages per minute. Add motion events and you’re looking at hundreds. If each of these is a direct HTTPS call to AWS, we’re paying for connection overhead that dwarfs the actual data. The Pi batches these into efficient chunks, reducing our cloud costs by roughly 80%.

Intelligence: The Pi isn’t just a relay—it’s a processing layer. It watches for patterns that individual cages can’t see. Three traps in Zone B all showing increased motion? That’s probably a cluster alert, not three unrelated events. Cage 042 suddenly silent after months of regular heartbeats? Proactively flag it as potentially offline, don’t wait for someone to notice.

The Pi runs our gateway software—a few thousand lines of Go code compiled into a single executable with no dependencies. Go was the obvious choice here: it cross-compiles to ARM trivially, it’s memory-efficient enough to run on Pi hardware with room to spare, and its concurrency model (goroutines and channels) maps perfectly to the “many devices, one processor” architecture we needed.

The gateway’s job, at its core, is simple: accept events from cages, decide what matters, and ship it to the cloud.

Project Structure

Before diving into code, let’s understand how everything is organized. The gateway isn’t a single monolithic file—it’s structured like a proper application:

/home/pi/smartcage-gateway/

├── cmd/

│ └── gateway/

│ └── main.go

├── internal/

│ ├── config/

│ │ └── config.go

│ ├── devices/

│ │ ├── manager.go

│ │ └── device.go

│ ├── events/

│ │ ├── processor.go

│ │ └── types.go

│ ├── mqtt/

│ │ └── publisher.go

│ ├── api/

│ │ └── server.go

│ └── storage/

│ └── local.go

├── configs/

│ └── config.yaml

├── certs/

│ ├── root-CA.crt

│ ├── gateway.cert.pem

│ └── gateway.private.key

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

└── Makefile

This layout follows Go best practices: cmd/ contains the main application

entry points, internal/ holds the packages that do the actual work, configs/

stores configuration files, and certs/ contains the AWS IoT certificates for

secure communication. Everything in internal/ can’t be imported by external

projects—it’s truly internal to this gateway.

Core Gateway Application

The main entry point is where all the components come together. Think of it as the conductor of an orchestra:

Importing Our Dependencies

// cmd/gateway/main.go

package main

import (

"context"

"log"

"os"

"os/signal"

"syscall"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/api"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/config"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/devices"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/events"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/mqtt"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/storage"

)

These imports tell you the story of what the gateway does: it loads configuration, manages devices, processes events, publishes to MQTT (AWS IoT), runs an API server, and handles local storage for resilience.

The Main Function: Bringing It All Together

func main() {

// Load configuration

cfg, err := config.Load("/home/pi/smartcage-gateway/configs/config.yaml")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to load config: %v", err)

}

// Initialize components

localStorage := storage.NewLocalStore(cfg.StoragePath)

deviceManager := devices.NewManager(localStorage)

mqttPublisher := mqtt.NewPublisher(cfg.AWS)

eventProcessor := events.NewProcessor(deviceManager, mqttPublisher, localStorage)

apiServer := api.NewServer(cfg.API, eventProcessor, deviceManager)

We’re building our system from the ground up. Local storage comes first—it’s the foundation everything else might fall back on if the network fails. The device manager tracks the state of every cage. The MQTT publisher handles cloud communication. The event processor is the brain that decides what to do with incoming data. And the API server lets cages talk to us.

Starting Services with Graceful Shutdown

// Create context for graceful shutdown

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

defer cancel()

// Start MQTT connection

if err := mqttPublisher.Connect(ctx); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to connect to AWS IoT: %v", err)

}

// Start event processor

go eventProcessor.Run(ctx)

// Start API server

go func() {

if err := apiServer.Start(); err != nil {

log.Printf("API server error: %v", err)

}

}()

log.Println("Smart Cage Gateway started successfully")

The context is Go’s way of managing cancellation—when we need to shut down, we

call cancel() and everything listening to that context knows to stop

gracefully. We start services with go routines—lightweight threads that run

concurrently. The MQTT connection blocks until established (we can’t do anything

without cloud connectivity), but the event processor and API server run in the

background.

Waiting for Shutdown Signals

// Wait for shutdown signal

sigChan := make(chan os.Signal, 1)

signal.Notify(sigChan, syscall.SIGINT, syscall.SIGTERM)

<-sigChan

log.Println("Shutting down gateway...")

cancel()

mqttPublisher.Disconnect()

apiServer.Stop()

log.Println("Gateway stopped")

}

This is the Unix way of handling termination: catch SIGINT (Ctrl+C) and SIGTERM (systemd asking us to stop), then shut down cleanly. We cancel the context (which tells all our goroutines to wrap up), explicitly disconnect MQTT and stop the API server, then exit. No orphaned connections, no corrupted writes, no drama.

Networking Configuration

Setting up networking in a warehouse is an exercise in pessimism. You assume everything will fail, then design around it.

The Pi runs as a WiFi access point, creating a dedicated network just for the cages. This might seem like extra complexity—why not just use the existing warehouse wifi?—but it’s actually a simplification. We control the network entirely. No IT department involvement, no IP address conflicts, no “someone unplugged the router” surprises.

WiFi Access Point Setup

Installing the Foundation

First, we need the right tools on the Pi:

#!/bin/bash

# setup_ap.sh - Configure Raspberry Pi as WiFi Access Point

# Install required packages

sudo apt update

sudo apt install -y hostapd dnsmasq

# Stop services during configuration

sudo systemctl stop hostapd

sudo systemctl stop dnsmasq

hostapd turns the Pi into an access point—think of it as software that makes

the WiFi chip act like a router. dnsmasq is our DHCP and DNS server—it hands

out IP addresses to connecting cages and resolves names like

gateway.smartcage.local.

Configuring a Static IP

The gateway needs a predictable address. Can’t have it changing every reboot:

# /etc/dhcpcd.conf

interface wlan0

static ip_address=192.168.4.1/24

nohook wpa_supplicant

We’re claiming 192.168.4.1 as our address, with a /24 subnet (meaning

everything from 192.168.4.0 to 192.168.4.255 is in our network). The

nohook wpa_supplicant line tells the Pi “don’t try to connect to other WiFi

networks on this interface—we’re running the show here.”

Setting Up the DHCP Server

Now we configure dnsmasq to hand out addresses to cages:

# /etc/dnsmasq.conf

interface=wlan0

dhcp-range=192.168.4.2,192.168.4.100,255.255.255.0,24h

domain=smartcage.local

address=/gateway.smartcage.local/192.168.4.1

We’re giving out addresses from .2 to .100—that’s 99 possible cages on one

gateway. The lease time is 24 hours (cages won’t be moving around, so we don’t

need short leases). And we’re setting up local DNS so cages can reach us via

name instead of remembering an IP.

Configuring the Access Point

Here’s where we define what cages will see when they scan for WiFi:

# /etc/hostapd/hostapd.conf

interface=wlan0

driver=nl80211

ssid=SmartCage-Gateway

hw_mode=g

channel=7

wmm_enabled=0

macaddr_acl=0

auth_algs=1

ignore_broadcast_ssid=0

wpa=2

wpa_passphrase=SecureP@ss2024!

wpa_key_mgmt=WPA-PSK

wpa_pairwise=TKIP

rsn_pairwise=CCMP

Breaking this down: we’re using the 2.4GHz band (hw_mode=g) on channel 7, with

WPA2 encryption. The SSID is broadcast (not hidden), and the password is

SecureP@ss2024!. In production, you’d change this per facility. Channel 7 is

middle-of-the-road—less crowded than 1, 6, or 11, but still reliable.

Making It Permanent

Finally, we wire everything up to start automatically:

# Point hostapd to config

sudo sed -i 's/#DAEMON_CONF=""/DAEMON_CONF="\/etc\/hostapd\/hostapd.conf"/' /etc/default/hostapd

# Enable IP forwarding

sudo sed -i 's/#net.ipv4.ip_forward=1/net.ipv4.ip_forward=1/' /etc/sysctl.conf

# Enable and start services

sudo systemctl unmask hostapd

sudo systemctl enable hostapd

sudo systemctl enable dnsmasq

sudo systemctl start hostapd

sudo systemctl start dnsmasq

The unmask is necessary because hostapd comes masked by default on Raspberry

Pi OS (legacy reasons). The enable commands make sure these services start on

boot. And start fires them up right now.

Internet Connectivity

The Pi broadcasts a network, cages connect to it, they get IP addresses automatically, and they can reach the gateway at a fixed address (192.168.4.1). No DNS lookups, no DHCP surprises, no external dependencies.

For internet connectivity, the Pi uses its ethernet port—a wired connection to the warehouse’s main network. This separation is intentional. The cage network is air-gapped from the corporate network, which makes security audits much simpler. A compromised ESP32 can’t reach anything except the gateway.

Configuring the Uplink

The Pi needs to reach the internet to talk to AWS. That happens over Ethernet:

# /etc/network/interfaces.d/eth0

auto eth0

iface eth0 inet dhcp

Simple: connect Ethernet cable, get an IP via DHCP from the warehouse network. Done.

Setting Up NAT

Now the tricky part: cages talk to the Pi on wlan0, but the Pi talks to the

internet on eth0. We need Network Address Translation to bridge these:

# NAT configuration for cage devices to access internet if needed

sudo iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o eth0 -j MASQUERADE

sudo iptables -A FORWARD -i eth0 -o wlan0 -m state --state RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

sudo iptables -A FORWARD -i wlan0 -o eth0 -j ACCEPT

The first rule says “traffic leaving on eth0 should be masqueraded”—rewritten

to look like it’s coming from the Pi’s eth0 IP. The second allows return

traffic back through. The third allows cages to initiate connections outward.

Together, these make the Pi act like a router.

Persisting the Rules

iptables rules disappear on reboot unless you save them:

# Save iptables rules

sudo sh -c "iptables-save > /etc/iptables.ipv4.nat"

# Add to /etc/rc.local before 'exit 0'

iptables-restore < /etc/iptables.ipv4.nat

We dump the rules to a file, then tell the system to reload them on boot via

rc.local—an old-school but reliable way to run commands at startup.

Boot Configuration & System Setup

Industrial systems need to survive power outages. When electricity comes back after a blackout, every component must start itself, reconnect, and resume operation without human intervention. This is non-negotiable.

On the Pi, we achieve this with systemd—the Linux service manager that handles starting programs at boot and restarting them if they crash.

Systemd Service

This is how we tell Linux “keep this program running forever”:

# /etc/systemd/system/smartcage-gateway.service

[Unit]

Description=Smart Cage IoT Gateway

After=network-online.target

Wants=network-online.target

StartLimitIntervalSec=0

The [Unit] section describes what we are. The After and Wants lines say

“don’t start until the network is up”—there’s no point starting a

cloud-connected service without connectivity. StartLimitIntervalSec=0 means

“no limit on restart attempts”—keep trying forever.

Service Configuration

[Service]

Type=simple

Restart=always

RestartSec=5

User=pi

WorkingDirectory=/home/pi/smartcage-gateway

ExecStart=/home/pi/smartcage-gateway/bin/gateway

Environment=GATEWAY_CONFIG=/home/pi/smartcage-gateway/configs/config.yaml

Type=simple means the process doesn’t fork or daemonize—it just runs.

Restart=always is the magic: crash, get killed, encounter an error? Systemd

restarts it. RestartSec=5 means wait 5 seconds between attempts (prevents

restart loops from thrashing the system). We run as user pi for security—no

need for root privileges.

Resource Limits

# Resource limits

MemoryMax=256M

CPUQuota=80%

These prevent a runaway gateway from taking down the entire Pi. Cap it at 256MB of RAM (plenty for Go) and 80% of one CPU core (leaving room for the OS). Good defensive programming.

Logging Setup

# Logging

StandardOutput=append:/var/log/smartcage/gateway.log

StandardError=append:/var/log/smartcage/gateway-error.log

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

All stdout goes to one log, stderr to another. The append means we don’t

truncate on restart—logs accumulate. The [Install] section with

WantedBy=multi-user.target means “start this at normal system boot, when we

reach multi-user mode.”

The key line is Restart=always. If the gateway crashes—bug, memory issue,

cosmic ray, whatever—systemd will restart it within five seconds. Combined with

our stateless design (all important data is either in the cloud or persisted to

disk), this means the system self-heals from almost any failure.

The cages are simpler. An ESP32 boots in about two seconds. The firmware immediately tries to connect to the gateway network, and if it can’t, it keeps trying forever. There’s no complex recovery logic because there’s no complex state. Sensor triggered? Send event. No connection? Buffer locally, retry later. Power cycle? Start fresh, no harm done.

Configuration File

Gateway Configuration

The YAML configuration file defines all the operational parameters:

# /home/pi/smartcage-gateway/configs/config.yaml

gateway:

id: "GW-WH001-01"

facility_id: "WH001"

log_level: "info"

api:

host: "0.0.0.0"

port: 8080

read_timeout: 30s

write_timeout: 30s

0.0.0.0 means “listen on all interfaces”—both the cage network and the

Ethernet connection. The 30-second timeouts are generous but necessary—image

uploads from cages can take time on a busy network.

Storage Configuration

storage:

path: "/home/pi/smartcage-gateway/data"

max_size_mb: 500

retention_days: 7

We’ll buffer up to 500MB locally—enough for thousands of events. After 7 days or when we hit the size limit, old data gets purged. This is purely a buffer for when cloud connectivity fails; we’re not trying to be a permanent database.

AWS IoT Configuration

aws:

region: "ap-south-1"

iot_endpoint: "xxxxxxxxxxxxxx-ats.iot.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com"

client_id: "smartcage-gateway-wh001"

topic_prefix: "smartcage"

cert_path: "/home/pi/smartcage-gateway/certs/gateway.cert.pem"

key_path: "/home/pi/smartcage-gateway/certs/gateway.private.key"

root_ca_path: "/home/pi/smartcage-gateway/certs/root-CA.crt"

qos: 1

The IoT endpoint is specific to your AWS account. QoS 1 means “at least once delivery”—messages might duplicate, but they won’t be lost. The certificates are how we authenticate to AWS—no API keys, no passwords, just cryptographic identity.

Event Processing Configuration

events:

batch_size: 10

batch_timeout: 5s

retry_attempts: 3

retry_delay: 2s

devices:

heartbeat_timeout: 600s

bait_refresh_interval: 168h # 7 days

We batch up to 10 events before sending, or send whatever we have after 5 seconds—whichever comes first. Three retry attempts with 2-second delays handle transient network hiccups. If we don’t hear from a cage in 10 minutes, we consider it offline. And bait expires after 7 days (168 hours).

Initialization Script

#!/bin/bash

# /home/pi/smartcage-gateway/scripts/init.sh

set -e

GATEWAY_HOME="/home/pi/smartcage-gateway"

LOG_DIR="/var/log/smartcage"

DATA_DIR="${GATEWAY_HOME}/data"

# Create directories

sudo mkdir -p ${LOG_DIR}

sudo chown pi:pi ${LOG_DIR}

mkdir -p ${DATA_DIR}

# Set permissions on certificates

chmod 600 ${GATEWAY_HOME}/certs/*.key

chmod 644 ${GATEWAY_HOME}/certs/*.pem

chmod 644 ${GATEWAY_HOME}/certs/*.crt

# Install service

sudo cp ${GATEWAY_HOME}/scripts/smartcage-gateway.service /etc/systemd/system/

sudo systemctl daemon-reload

sudo systemctl enable smartcage-gateway

sudo systemctl start smartcage-gateway

echo "Smart Cage Gateway initialized successfully"

Device Signal Processing

All that the device can do is publish events. They have no meaning unless they are identified, interpreted and processed properly.

API Server for Receiving Device Events

Each cage communicates with the gateway over plain HTTP—RESTful endpoints accepting JSON payloads. We considered MQTT (the protocol du jour for IoT) but rejected it for simplicity. HTTP works fine for our message rates, every developer knows how to debug it, and the ESP32 has excellent HTTP client libraries.

The message format is deliberately flat and explicit. No nested objects, no arrays, no optional fields that might or might not appear. Every message contains everything we need to process it in isolation. This makes debugging trivial—you can literally read the JSON and understand what happened—and processing stateless on the server side.

Server Structure

The API server is where cages post their events:

// internal/api/server.go

package api

import (

"context"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

"time"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/devices"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/events"

)

type Server struct {

config Config

httpServer *http.Server

eventProcessor *events.Processor

deviceManager *devices.Manager

}

type Config struct {

Host string `yaml:"host"`

Port int `yaml:"port"`

ReadTimeout time.Duration `yaml:"read_timeout"`

WriteTimeout time.Duration `yaml:"write_timeout"`

}

The Server struct holds everything we need: configuration, the actual HTTP

server, and references to our event processor and device manager. Keeping these

as fields means we don’t need global variables—better for testing and cleaner

code.

Initializing the Server

func NewServer(cfg Config, ep *events.Processor, dm *devices.Manager) *Server {

s := &Server{

config: cfg,

eventProcessor: ep,

deviceManager: dm,

}

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/api/events", s.handleEvent)

mux.HandleFunc("/api/devices", s.handleDevices)

mux.HandleFunc("/api/devices/", s.handleDeviceAction)

mux.HandleFunc("/health", s.handleHealth)

s.httpServer = &http.Server{

Addr: fmt.Sprintf("%s:%d", cfg.Host, cfg.Port),

Handler: mux,

ReadTimeout: cfg.ReadTimeout,

WriteTimeout: cfg.WriteTimeout,

}

return s

}

We’re setting up a standard HTTP multiplexer with four endpoints: /api/events

for incoming cage data, /api/devices for listing all devices, /api/devices/

for device-specific actions, and /health for monitoring. The timeout

configuration prevents slow clients from tying up server resources.

Handling Incoming Events

This is the hot path—where every cage event lands:

func (s *Server) handleEvent(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if r.Method != http.MethodPost {

http.Error(w, "Method not allowed", http.StatusMethodNotAllowed)

return

}

var evt events.DeviceEvent

if err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&evt); err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed to decode event: %v", err)

http.Error(w, "Invalid JSON payload", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

// Set server-side timestamp

evt.ReceivedAt = time.Now().UTC()

We only accept POST requests (GETs don’t make sense for submitting data). We decode the JSON directly from the request body—no need to read it all into memory first. And we add a server-side timestamp—never fully trust client clocks, especially on devices that might have been powered off for days.

Validation and Processing

// Validate required fields

if evt.DeviceID == "" || evt.EventType == "" {

http.Error(w, "Missing required fields", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

// Process the event

if err := s.eventProcessor.Submit(evt); err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed to process event from %s: %v", evt.DeviceID, err)

http.Error(w, "Internal server error", http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

// Update device state

s.deviceManager.UpdateDevice(evt)

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(map[string]string{

"status": "accepted",

"event_id": evt.EventID,

})

}

Basic validation: device ID and event type are mandatory. Submit to the event processor (which might batch it, analyze it, whatever). Update the device manager’s view of this cage’s state. Send back a 200 OK with the event ID so the cage knows we got it. Fast, simple, reliable.

Device Listing Endpoint

func (s *Server) handleDevices(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if r.Method != http.MethodGet {

http.Error(w, "Method not allowed", http.StatusMethodNotAllowed)

return

}

devices := s.deviceManager.GetAllDevices()

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(devices)

}

This one’s simple: when asked, dump out the current state of all known devices. Useful for debugging and for dashboards that want a snapshot.

Device Actions Endpoint

func (s *Server) handleDeviceAction(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// Handle device-specific actions like bait refresh acknowledgment

deviceID := r.URL.Path[len("/api/devices/"):]

switch r.Method {

case http.MethodPost:

var action struct {

Action string `json:"action"`

}

if err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&action); err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Invalid request", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

switch action.Action {

case "refresh_bait":

s.deviceManager.RecordBaitRefresh(deviceID)

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

case "reset_trap":

s.deviceManager.ResetTrap(deviceID)

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

default:

http.Error(w, "Unknown action", http.StatusBadRequest)

}

default:

http.Error(w, "Method not allowed", http.StatusMethodNotAllowed)

}

}

This handles commands to devices. When maintenance staff refreshes bait or resets a trap, the dashboard POSTs here. We parse out the device ID from the URL path and dispatch to the appropriate action. In a more sophisticated system, these actions would queue actual commands to send back to the ESP32s.

Health Check

func (s *Server) handleHealth(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(map[string]interface{}{

"status": "healthy",

"timestamp": time.Now().UTC(),

"devices": s.deviceManager.GetDeviceCount(),

})

}

Monitoring systems love health checks. Returns 200 OK if we’re running, along with some basic stats. If this endpoint stops responding, something’s very wrong.

Server Lifecycle

func (s *Server) Start() error {

log.Printf("Starting API server on %s", s.httpServer.Addr)

return s.httpServer.ListenAndServe()

}

func (s *Server) Stop() error {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 10*time.Second)

defer cancel()

return s.httpServer.Shutdown(ctx)

}

Start() blocks until the server stops (which only happens on error or

shutdown). Stop() does a graceful shutdown: stop accepting new connections,

finish processing active requests, but give up after 10 seconds if something’s

hung.

Data Collation & Event Detection

An important step in data processing is collating the data to make sense out of it.

Event Types and Processing Logic

Defining Our Event Universe

First, we enumerate everything that can happen:

// internal/events/types.go

package events

import "time"

type EventType string

const (

EventTrapTriggered EventType = "TRAP_TRIGGERED"

EventMotionDetected EventType = "MOTION_DETECTED"

EventHeartbeat EventType = "HEARTBEAT"

EventBaitRefreshed EventType = "BAIT_REFRESHED"

EventLowBattery EventType = "LOW_BATTERY"

EventDeviceOffline EventType = "DEVICE_OFFLINE"

EventBaitExpired EventType = "BAIT_EXPIRED"

)

Using constants instead of bare strings prevents typos and makes refactoring easier. The type system enforces correctness—you can’t accidentally pass “TRAP_TRIGGERD” (with a typo).

The Device Event Structure

type DeviceEvent struct {

EventID string `json:"event_id"`

DeviceID string `json:"device_id"`

FacilityID string `json:"facility_id"`

Zone string `json:"zone"`

EventType EventType `json:"event_type"`

Timestamp int64 `json:"timestamp"`

ReceivedAt time.Time `json:"received_at"`

// Optional fields based on event type

BatteryLevel float64 `json:"battery_level,omitempty"`

TrapStatus string `json:"trap_status,omitempty"`

MotionCount int `json:"motion_count,omitempty"`

WifiRSSI int `json:"wifi_rssi,omitempty"`

ImageData string `json:"image_data,omitempty"`

LastBaitRefresh int64 `json:"last_bait_refresh,omitempty"`

}

The omitempty tags mean these fields disappear from JSON if they’re

zero/empty. A heartbeat doesn’t need ImageData, so why waste bytes

transmitting an empty string? This makes our payloads leaner.

The Cloud Event Wrapper

type CloudEvent struct {

GatewayID string `json:"gateway_id"`

FacilityID string `json:"facility_id"`

Timestamp time.Time `json:"timestamp"`

Events []DeviceEvent `json:"events"`

}

When we send data to AWS, we batch multiple device events into a single cloud event. This is more efficient—one MQTT message can carry 10 cage events, reducing overhead.

Priority System

// Priority levels for event processing

type Priority int

const (

PriorityLow Priority = 0

PriorityNormal Priority = 1

PriorityHigh Priority = 2

PriorityCritical Priority = 3

)

func (e DeviceEvent) GetPriority() Priority {

switch e.EventType {

case EventTrapTriggered:

return PriorityCritical

case EventLowBattery, EventDeviceOffline, EventBaitExpired:

return PriorityHigh

case EventMotionDetected:

return PriorityNormal

default:

return PriorityLow

}

}

Not all events are equally urgent. A trap trigger demands immediate attention—someone needs to go collect that rat. Low battery is important but not instant. Motion detection is just informational. The priority system lets us bypass batching for critical events—they go to the cloud immediately.

Event Processor

Processor Structure

The event processor is the engine that makes decisions about incoming data:

// internal/events/processor.go

package events

import (

"context"

"log"

"sync"

"time"

"github.com/google/uuid"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/devices"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/mqtt"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/storage"

)

type Processor struct {

deviceManager *devices.Manager

publisher *mqtt.Publisher

localStorage *storage.LocalStore

eventChan chan DeviceEvent

batchSize int

batchTimeout time.Duration

// Derived event detection

mu sync.Mutex

motionWindows map[string]*MotionWindow

}

type MotionWindow struct {

DeviceID string

Count int

FirstSeen time.Time

LastSeen time.Time

}

The eventChan is a buffered channel—events queue up here waiting to be

processed. The motionWindows map tracks activity patterns per device, letting

us detect unusual clustering. The sync.Mutex protects that map from concurrent

access—multiple goroutines will be touching it.

Creating a Processor

type ProcessorConfig struct {

BatchSize int `yaml:"batch_size"`

BatchTimeout time.Duration `yaml:"batch_timeout"`

RetryAttempts int `yaml:"retry_attempts"`

RetryDelay time.Duration `yaml:"retry_delay"`

}

func NewProcessor(dm *devices.Manager, pub *mqtt.Publisher, ls *storage.LocalStore) *Processor {

return &Processor{

deviceManager: dm,

publisher: pub,

localStorage: ls,

eventChan: make(chan DeviceEvent, 1000),

batchSize: 10,

batchTimeout: 5 * time.Second,

motionWindows: make(map[string]*MotionWindow),

}

}

The channel buffer of 1000 means we can queue that many events before blocking. In practice, we process faster than cages generate events, but the buffer handles burst traffic—like when the gateway boots up and 50 cages send heartbeats simultaneously.

Submitting Events for Processing

func (p *Processor) Submit(evt DeviceEvent) error {

// Generate event ID if not present

if evt.EventID == "" {

evt.EventID = uuid.New().String()

}

// Enrich event with derived data

p.enrichEvent(&evt)

// Check for derived events

derivedEvents := p.detectDerivedEvents(evt)

Before queueing an event, we do some preprocessing. Generate a unique ID if the cage didn’t provide one (defensive programming). Enrich it with server-side analysis. And see if this event should trigger synthetic events—like detecting that bait has expired based on the timestamp in a heartbeat.

Queueing Events

// Submit original event

select {

case p.eventChan <- evt:

default:

// Channel full - store locally for retry

p.localStorage.StoreEvent(evt)

log.Printf("Event channel full, stored locally: %s", evt.EventID)

}

// Submit any derived events

for _, de := range derivedEvents {

p.eventChan <- de

}

return nil

}

The select with a default case is non-blocking: try to send to the channel,

but if it’s full, don’t wait—store locally instead. This prevents cage requests

from hanging if we’re overwhelmed. Derived events go straight to the channel—we

generated them, they’re not coming from cages, so they’re trusted.

Event Enrichment

func (p *Processor) enrichEvent(evt *DeviceEvent) {

// Add gateway timestamp

evt.ReceivedAt = time.Now().UTC()

// Check battery level and generate alert if low

if evt.BatteryLevel > 0 && evt.BatteryLevel < 20 {

log.Printf("Low battery alert for device %s: %.1f%%",

evt.DeviceID, evt.BatteryLevel)

}

}

Simple but important: add our timestamp, check for low battery. In a production system, you might add more analysis here—signal quality trends, unusual timing patterns, whatever makes sense for your domain.

Detecting Derived Events

This is where we get smart—spotting problems the cages don’t explicitly report:

func (p *Processor) detectDerivedEvents(evt DeviceEvent) []DeviceEvent {

var derived []DeviceEvent

// Detect bait expiration

if evt.EventType == EventHeartbeat && evt.LastBaitRefresh > 0 {

baitAge := time.Since(time.Unix(evt.LastBaitRefresh/1000, 0))

if baitAge > 7*24*time.Hour { // 7 days

derived = append(derived, DeviceEvent{

EventID: uuid.New().String(),

DeviceID: evt.DeviceID,

FacilityID: evt.FacilityID,

Zone: evt.Zone,

EventType: EventBaitExpired,

Timestamp: time.Now().UnixMilli(),

ReceivedAt: time.Now().UTC(),

})

}

}

A heartbeat carries the last bait refresh timestamp. If that’s more than 7 days

ago, we synthesize a BaitExpired event. The cage doesn’t need to know about

this rule—we centralize the logic on the gateway where it’s easier to update.

Detecting Activity Patterns

// Detect unusual motion patterns

if evt.EventType == EventMotionDetected {

p.mu.Lock()

window, exists := p.motionWindows[evt.DeviceID]

if !exists {

window = &MotionWindow{

DeviceID: evt.DeviceID,

FirstSeen: time.Now(),

}

p.motionWindows[evt.DeviceID] = window

}

window.Count++

window.LastSeen = time.Now()

// Alert if high motion in short window (potential infestation hotspot)

if window.Count > 50 && time.Since(window.FirstSeen) < time.Hour {

log.Printf("High activity detected at %s: %d events in %v",

evt.DeviceID, window.Count, time.Since(window.FirstSeen))

}

// Reset window after 1 hour

if time.Since(window.FirstSeen) > time.Hour {

window.Count = 1

window.FirstSeen = time.Now()

}

p.mu.Unlock()

}

return derived

}

We track motion events over a sliding 1-hour window. If we see more than 50 events in an hour at one location, that’s unusual—log it, potentially alert facilities management. This kind of pattern detection is why we process at the edge rather than sending everything raw to the cloud.

The Main Event Processing Loop

This goroutine runs continuously, consuming events from the channel:

func (p *Processor) Run(ctx context.Context) {

ticker := time.NewTicker(p.batchTimeout)

defer ticker.Stop()

var batch []DeviceEvent

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

// Flush remaining events

if len(batch) > 0 {

p.publishBatch(batch)

}

return

The ctx.Done() channel closes when the gateway is shutting down. We flush any

pending events before exiting—don’t lose data just because we’re stopping.

Receiving Events

case evt := <-p.eventChan:

batch = append(batch, evt)

// Publish immediately for critical events

if evt.GetPriority() == PriorityCritical {

p.publishBatch(batch)

batch = nil

continue

}

// Publish when batch is full

if len(batch) >= p.batchSize {

p.publishBatch(batch)

batch = nil

}

Critical events bypass batching—they go out immediately. For everything else, we

accumulate until we hit batchSize (10 events), then send them all at once.

This is the efficiency trade-off: lower latency for urgent events, higher

throughput for routine ones.

Timeout-Based Publishing

case <-ticker.C:

// Publish on timeout even if batch not full

if len(batch) > 0 {

p.publishBatch(batch)

batch = nil

}

// Also retry any locally stored events

p.retryStoredEvents()

}

}

}

The ticker fires every 5 seconds. If we have any events (even just one), send them—don’t let them sit forever waiting for a full batch. And use this opportunity to retry any events we had to store locally due to connectivity issues.

Publishing a Batch

func (p *Processor) publishBatch(events []DeviceEvent) {

if len(events) == 0 {

return

}

cloudEvent := CloudEvent{

GatewayID: "GW-WH001-01", // From config

FacilityID: events[0].FacilityID,

Timestamp: time.Now().UTC(),

Events: events,

}

if err := p.publisher.Publish(cloudEvent); err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed to publish batch: %v", err)

// Store locally for retry

for _, evt := range events {

p.localStorage.StoreEvent(evt)

}

} else {

log.Printf("Published batch of %d events", len(events))

}

}

Wrap the events in a CloudEvent envelope, try to publish. If it fails (network

down, AWS unreachable, whatever), don’t lose the data—store locally. When

connectivity returns, retryStoredEvents() will pick them up.

Retrying Failed Events

func (p *Processor) retryStoredEvents() {

events := p.localStorage.GetPendingEvents(p.batchSize)

if len(events) == 0 {

return

}

log.Printf("Retrying %d stored events", len(events))

p.publishBatch(events)

}

Pull a batch of stored events, try publishing again. If it succeeds, great—they’re on their way to the cloud. If it fails, they get stored again. Eventually connectivity returns and everything drains.

Cloud Publishing with AWS IoT Core

The gateway talks to AWS using MQTT—a lightweight pub/sub protocol designed for unreliable networks and constrained devices. Think of it as the postal service for IoT: you hand messages to a broker, and it makes sure they reach their destination.

MQTT Publisher

Publisher Structure and Configuration

First, let’s look at how we organize the MQTT client:

// internal/mqtt/publisher.go

package mqtt

import (

"context"

"crypto/tls"

"crypto/x509"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

"os"

"sync"

"time"

MQTT "github.com/eclipse/paho.mqtt.golang"

"smartcage-gateway/internal/events"

)

type Publisher struct {

config AWSConfig

client MQTT.Client

mu sync.Mutex

connected bool

}

type AWSConfig struct {

Region string `yaml:"region"`

IoTEndpoint string `yaml:"iot_endpoint"`

ClientID string `yaml:"client_id"`

TopicPrefix string `yaml:"topic_prefix"`

CertPath string `yaml:"cert_path"`

KeyPath string `yaml:"key_path"`

RootCAPath string `yaml:"root_ca_path"`

QoS int `yaml:"qos"`

}

The Publisher wraps the MQTT client and adds thread-safe connection tracking.

The mutex protects the connected boolean—multiple goroutines will be checking

this, and Go requires explicit synchronization for shared state.

Creating a Publisher Instance

func NewPublisher(cfg AWSConfig) *Publisher {

return &Publisher{

config: cfg,

}

}

Simple constructor. We don’t connect yet—that happens explicitly in Connect().

This separation of creation and connection is important for testing and

initialization ordering.

Establishing the Connection

The connection setup is where the security happens:

func (p *Publisher) Connect(ctx context.Context) error {

tlsConfig, err := p.newTLSConfig()

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to create TLS config: %w", err)

}

opts := MQTT.NewClientOptions()

opts.AddBroker(fmt.Sprintf("ssl://%s:8883", p.config.IoTEndpoint))

opts.SetClientID(p.config.ClientID)

opts.SetTLSConfig(tlsConfig)

opts.SetKeepAlive(30 * time.Second)

opts.SetAutoReconnect(true)

opts.SetMaxReconnectInterval(5 * time.Minute)

We’re connecting over SSL/TLS on port 8883 (the secure MQTT port). The

SetClientID uniquely identifies this gateway to AWS. The 30-second keepalive

means “send a ping every 30 seconds to prove we’re alive.” Auto-reconnect with

exponential backoff (capping at 5 minutes) handles network hiccups gracefully.

Connection Event Handlers

These callbacks tell us what’s happening with the connection:

opts.SetOnConnectHandler(func(c MQTT.Client) {

log.Println("Connected to AWS IoT Core")

p.mu.Lock()

p.connected = true

p.mu.Unlock()

})

opts.SetConnectionLostHandler(func(c MQTT.Client, err error) {

log.Printf("Connection lost: %v", err)

p.mu.Lock()

p.connected = false

p.mu.Unlock()

})

When we successfully connect, set the flag and log it. When we lose connection, clear the flag and log why. These callbacks run in the MQTT library’s goroutines, so we use the mutex to safely update our state.

Starting the Client

p.client = MQTT.NewClient(opts)

token := p.client.Connect()

if token.Wait() && token.Error() != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to connect: %w", token.Error())

}

return nil

}

The Paho MQTT library is asynchronous—Connect() returns a token immediately,

and you wait on the token for completion. If the token returns an error,

connection failed. Otherwise, we’re live.

TLS Configuration: The Security Layer

This is where we load our certificates and configure encryption:

func (p *Publisher) newTLSConfig() (*tls.Config, error) {

certPool := x509.NewCertPool()

ca, err := os.ReadFile(p.config.RootCAPath)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to read root CA: %w", err)

}

certPool.AppendCertsFromPEM(ca)

First, we load the root CA certificate—this is how we verify we’re actually talking to AWS and not some imposter. The CA cert is the trust anchor of the entire security chain.

Loading Client Certificates

cert, err := tls.LoadX509KeyPair(p.config.CertPath, p.config.KeyPath)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to load cert/key: %w", err)

}

return &tls.Config{

RootCAs: certPool,

Certificates: []tls.Certificate{cert},

MinVersion: tls.VersionTLS12,

}, nil

}

The client certificate and private key are this gateway’s identity. AWS IoT validates the certificate against its registry and grants access based on attached policies. TLS 1.2 minimum ensures we’re using strong encryption—no obsolete protocols.

Publishing Events to AWS

This is the main method—getting our data to the cloud:

func (p *Publisher) Publish(event events.CloudEvent) error {

p.mu.Lock()

connected := p.connected

p.mu.Unlock()

if !connected {

return fmt.Errorf("not connected to broker")

}

Check connection status first. If we’re not connected, fail fast—don’t try to publish. The caller (event processor) will store locally and retry later.

Serializing and Routing

payload, err := json.Marshal(event)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to marshal event: %w", err)

}

// Determine topic based on event priority

topic := p.determineTopic(event)

token := p.client.Publish(topic, byte(p.config.QoS), false, payload)

if token.Wait() && token.Error() != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to publish: %w", token.Error())

}

log.Printf("Published to %s: %d events", topic, len(event.Events))

return nil

}

Convert the event to JSON, determine which topic to publish to (more on that in

a moment), then publish with our configured QoS. The false parameter means

“not retained”—this is ephemeral event data, not state that needs to persist.

Smart Topic Routing

Different event types go to different topics for efficient processing:

func (p *Publisher) determineTopic(event events.CloudEvent) string {

// Route critical events to dedicated topic for faster processing

for _, e := range event.Events {

if e.GetPriority() == events.PriorityCritical {

return fmt.Sprintf("%s/%s/alerts",

p.config.TopicPrefix, event.FacilityID)

}

}

return fmt.Sprintf("%s/%s/events", p.config.TopicPrefix, event.FacilityID)

}

If the batch contains any critical events (trap triggered, device offline),

route to the alerts topic. Otherwise, use the general events topic. In AWS,

we can set up different Lambda functions subscribed to different topics—letting

us process critical alerts with higher priority and resources.

Disconnecting Cleanly

func (p *Publisher) Disconnect() {

if p.client != nil && p.client.IsConnected() {

p.client.Disconnect(1000)

log.Println("Disconnected from AWS IoT Core")

}

}

func (p *Publisher) IsConnected() bool {

p.mu.Lock()

defer p.mu.Unlock()

return p.connected

}

The 1000 parameter to Disconnect() means “wait up to 1000 milliseconds for

in-flight messages to complete.” This ensures we don’t cut off a publish in

progress. The IsConnected() method safely checks status from any goroutine.

AWS Lambda Functions

Lambda functions are where our data lands in the cloud. They’re serverless—AWS runs them on demand, scales them automatically, and we only pay for actual execution time. Perfect for event-driven IoT workloads.

Event Ingestion Lambda

This Lambda receives MQTT messages from IoT Core and persists them to DynamoDB.

Imports and Initialization

// lambda/ingest/main.go

package main

import (

"context"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

"os"

"time"

"github.com/aws/aws-lambda-go/events"

"github.com/aws/aws-lambda-go/lambda"

"github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go-v2/config"

"github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go-v2/service/dynamodb"

"github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go-v2/service/dynamodb/types"

"github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go-v2/feature/dynamodb/attributevalue"

)

var (

ddbClient *dynamodb.Client

tableName string

alertTable string

)

Global variables in Lambda are initialized once per container and reused across invocations. This is a performance optimization—we don’t want to create a new DynamoDB client on every single event.

Defining Our Data Structures

type CloudEvent struct {

GatewayID string `json:"gateway_id"`

FacilityID string `json:"facility_id"`

Timestamp time.Time `json:"timestamp"`

Events []DeviceEvent `json:"events"`

}

type DeviceEvent struct {

EventID string `json:"event_id"`

DeviceID string `json:"device_id"`

FacilityID string `json:"facility_id"`

Zone string `json:"zone"`

EventType string `json:"event_type"`

Timestamp int64 `json:"timestamp"`

BatteryLevel float64 `json:"battery_level,omitempty"`

TrapStatus string `json:"trap_status,omitempty"`

MotionCount int `json:"motion_count,omitempty"`

WifiRSSI int `json:"wifi_rssi,omitempty"`

ImageData string `json:"image_data,omitempty"`

}

These mirror the structures we defined on the gateway. Consistency across the stack makes debugging easier—the same JSON that leaves the Pi arrives here unchanged.

DynamoDB Record Structure

DynamoDB is a NoSQL database, but we still need a schema for our access patterns:

// DynamoDB record structure

type EventRecord struct {

PK string `dynamodbav:"PK"` // DEVICE#<device_id>

SK string `dynamodbav:"SK"` // EVENT#<timestamp>#<event_id>

GSI1PK string `dynamodbav:"GSI1PK"` // FACILITY#<facility_id>

GSI1SK string `dynamodbav:"GSI1SK"` // <event_type>#<timestamp>

EventID string `dynamodbav:"event_id"`

DeviceID string `dynamodbav:"device_id"`

FacilityID string `dynamodbav:"facility_id"`

Zone string `dynamodbav:"zone"`

EventType string `dynamodbav:"event_type"`

Timestamp int64 `dynamodbav:"timestamp"`

BatteryLevel float64 `dynamodbav:"battery_level,omitempty"`

TrapStatus string `dynamodbav:"trap_status,omitempty"`

MotionCount int `dynamodbav:"motion_count,omitempty"`

WifiRSSI int `dynamodbav:"wifi_rssi,omitempty"`

ImageS3Key string `dynamodbav:"image_s3_key,omitempty"`

TTL int64 `dynamodbav:"ttl"`

CreatedAt string `dynamodbav:"created_at"`

}

The PK (partition key) and SK (sort key) define how data is physically

stored. By using DEVICE#<id> as PK, all events for a device are co-located for

fast retrieval. The GSI1 keys enable querying by facility and event type—a

Global Secondary Index with a different key structure.

Lambda Initialization

func init() {

cfg, err := config.LoadDefaultConfig(context.Background())

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to load AWS config: %v", err)

}

ddbClient = dynamodb.NewFromConfig(cfg)

tableName = os.Getenv("EVENTS_TABLE")

alertTable = os.Getenv("ALERTS_TABLE")

if tableName == "" {

tableName = "smartcage-events"

}

}

The init() function runs once when Lambda creates a new container. We load AWS

credentials (automatically provided by the Lambda execution role), create our

DynamoDB client, and read configuration from environment variables. If

EVENTS_TABLE isn’t set, we default to a sensible name.

The Handler Function

This is the entry point—invoked by AWS for each MQTT message:

func handler(ctx context.Context, iotEvent events.IoTCoreCustomAuthorizerRequest) error {

// Parse the incoming IoT message

var cloudEvent CloudEvent

if err := json.Unmarshal([]byte(iotEvent.Token), &cloudEvent); err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed to parse event: %v", err)

return err

}

log.Printf("Processing %d events from gateway %s",

len(cloudEvent.Events), cloudEvent.GatewayID)

AWS IoT Core triggers this Lambda by passing the MQTT message payload. We

unmarshal the JSON into our CloudEvent structure, log what we’re processing,

then iterate through the individual device events.

Processing Each Event

// Process each event

for _, evt := range cloudEvent.Events {

if err := processEvent(ctx, evt); err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed to process event %s: %v", evt.EventID, err)

// Continue processing other events

}

}

return nil

}